Bordwell on Andrew Sarris

09 07, 12

From David Bordwell’s blog Observations on Film Art

The death of Andrew Sarris last week isn’t just a saddening moment for those of us who admire exhilarating film criticism. It also reminds us how much American culture can owe to a single person.

Everyone who writes about Sarris writes about how they came to know his work. It was that powerful, and if it hit you young, you were never the same. (You never hear about the sixty-year-old who suddenly becomes an auteurist.) The period of his greatest impact was the 1960s-1970s when, to borrow a phrase from Dave Kehr, movies mattered. But his influence has lingered, powerfully, a lot longer.

I think that the best way to honor Sarris is to take his ideas–not just his opinions, but his ideas–seriously, so that’s what I’ve tried to do in this tribute. First, though, some comments that are obligatory in any discussion of Sarris.

The death of Andrew Sarris last week isn’t just a saddening moment for those of us who admire exhilarating film criticism. It also reminds us how much American culture can owe to a single person.

Everyone who writes about Sarris writes about how they came to know his work. It was that powerful, and if it hit you young, you were never the same. (You never hear about the sixty-year-old who suddenly becomes an auteurist.) The period of his greatest impact was the 1960s-1970s when, to borrow a phrase from Dave Kehr, movies mattered. But his influence has lingered, powerfully, a lot longer.

I think that the best way to honor Sarris is to take his ideas–not just his opinions, but his ideas–seriously, so that’s what I’ve tried to do in this tribute. First, though, some comments that are obligatory in any discussion of Sarris.

Obligatory autobiography 1

1963: When I was sixteen I wrote to various film magazines and asked for sample issues as a “prospective subscriber.” Surprisingly, several answered, and I amassed a few copies of Film Quarterly, Films and Filming, and Movie. No gift from the land of film journals was more propitious than that fateful issue 28 of Film Culture entitled “American Directors.” It was the first draft of what would become Sarris’ 1968 book, The American Cinema.

Issue 28 was a dangerous item to give a kid. It contained what Georgie Minafer calls “touchy chemicals.” At first I was baffled. There were those famous categories: How to distinguish “Lightly Likeable” from “Less Than Meets the Eye”? Who were Budd Boetticher, Tay Garnett, and John M. Stahl? What did it mean to say that Robert Montgomery “executed a charming champ-contre-champ joke in Once More, My Darling”? To me it was all Expressive Esoterica. Here was a cave of mysteries, but it hinted at treasures.

Sarris’s filmographies were packed with titles I’d never heard of. How could I catch up? Around 1955, the studios had begun selling their pre-1948 titles to local television stations. By the next year, people living in major cities could tune in five or six movies a day. At the forefront of TV sales was the financially precarious RKO, which sold over seven hundred titles to an outfit called C & C. C & C packaged the library as 16mm TV prints under the rubric of “Movietime.”

Auteurism owes a good deal to the 1950s-1960s equivalent of home video, the thousands of 16mm prints floating around local TV stations. In Manhattan, WOR-TV screened their films under the rubric “Million Dollar Movie.” The same film might run once or twice every night for a week (and twice or more on weekends). Without benefit of WOR or New York’s revival houses, I was still able to use Rochester television to sample some of the titles that Sarris had listed, especially those given in big caps. (Italicizing must-see items didn’t show up until the book version.) Sarris’s essay, “Citizen Kane: The American Baroque,” was published in Film Culture in 1956, the same year that the RKO library began to be syndicated and Kane was reissued in theatres around the country.

I did wind up subscribing to Film Culture. It was the least I could do to pay them back.

Obligatory autobiography 2

Fall 1965: At a state college up the Hudson, the English department hosted a debate on contemporary American movies. The adversaries were Pauline Kael and Andrew Sarris, both just coming into the national spotlight. One freshman came early and sat with comic earnestness in the front row, a spot he would fetishize later.

Kael was witty and acerbic, tossing off judgments with a wave of her cigarette holder. The Cincinnati Kid was the best of the current crop; Jewison showed great promise. She was riding high because I Lost It at the Movies had come out that spring and was greeted with hosannas. The New Yorker review contrasted her with “the far-out Sarris.”

He didn’t look so far-out. In a crumpled suit, he was resolutely uncharismatic, looking mildly unhappy to be dragged blinking out of the Thalia and shipped upstate. He talked fast, interrupted himself, and, finding few recent movies to praise, celebrated Max Ophuls and Jean Renoir. He delivered enigmatic observations like, “All movies should probably be in color.”

At evening’s end, I knew which camp I belonged in. I got an appropriately nerdy autograph for my Film Culture issue: “Cinecerely yours, Andrew Sarris.” More important, I exulted in a sense that my almost grim obsession with movies had been validated. Not for some time would I realize that I had enlisted, to put it melodramatically, in a fight for American film culture. The battle lines were drawn more sharply in Manhattan than in Albany, but everywhere one thing was clear. Kael was clearly the standard bearer for them, and Sarris was ours.

Obligatory comparison: S vs. K

Who were the them? They were the hip intellectuals who enjoyed a night at the movies. At faculty parties throughout the 1970s I had to check myself when professors of lit or law asked me if I didn’t find Kael’s review that week intoxicating. And she writes so well! As chief New Yorker critic, Kael became the grand tastemaker, a person even filmmakers courted. But who would try to curry favor with the guy who wrote for the Village Voice? It reminds you of the joke about the starlet so dumb she slept with the screenwriter.

Of course like all acolytes we overplayed the differences. Both Kael and Sarris loved classic studio cinema, the performers and scripts as much as the directorial handling. Both critics bemoaned Soviet montage and what they saw as its descendant, the overbusy technique of the 1960s. Both deplored stylistic aggressiveness (the Tony Richardson Syndrome) and both idolized Renoir. Both loved lyricism.

According to us, though, Kael wrote for those who dug movies, while Sarris wrote for those who loved cinema—the medium itself, or rather an exalted idea of the medium’s potential, an ideal form of expression at once dramatic, poetic, pictorial, and musical. He saw each film as bearing witness to the promise of what cinema might be, and he looked in even the tawdriest products for something approximating his dreams. Despite his enthusiasms, he tried for detachment, viewing the latest movie from some unpredictable historical perspective.

Kael famously declared that she watched a new film only once, because that was the way her readers would consume it. But who, we thought, would want to write about a movie after seeing it only once? Mightn’t it reveal some strengths or weaknesses on a second viewing? If it was a good movie, who wouldn’t want to see it more than once? In that same freshman semester, when there were still first-run double features, I sat through The Glory Guys twice in order to watch Help! three times. And that wasn’t even a particularly good movie.

Kael pounced on faults, Sarris savored beauties. Kael made each weak film seem like a blow to her intelligence. Sarris, although he could be harsh, tended to forgive. He taught that it was better to leave a door open than to write someone off—even Bergman, whom some of us would never learn to like until Persona, some not until Fanny and Alexander. Sarris subordinated his personality to that of the movie and its director, which made him seem less fiery than his uptown counterpart; but his attitude suited our own somewhat adolescent amorphousness of character. The arrogant certainty of our tastes was, paradoxically, born of a passionate humility, a sense of serving wise masters named Dreyer, Murnau, Mizoguchi.

Rethinking film history

Sarris is known primarily as the man who gave us the American version of auteurism, or what he called “the auteur theory.” It wasn’t a theory of cinema as such, but rather a heuristic approach to criticism: tips on what to think about and look for when you wanted to plumb a movie’s artistry. But initially, auteurism claimed to be a theory of something else. The opening chapter of The American Cinema is called “Toward a Theory of Film History.”

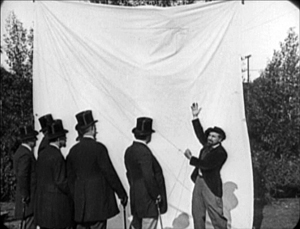

In Sarris’s day, most people writing about the history of film as an art accepted a notion of technical progress. According to this view, filmmakers became significant by contributing toward the development of the medium. Editing emerged through the efforts of Méliès, Porter, and Griffith, followed by the Russian Montage directors. Various national schools revealed more possibilities of the medium: fantasy and abstraction with the German Expressionists, derangement of sense with the Surrealists.

When sound arrived, a few directors (Clair, Mamoulian, Hitchcock) explored the stylized possibilities of that new technology. But many historians, considering that cinema was inherently a visual medium, declared sound an unwanted intrusion. Clearly, the great days of cinematic artistry were over. Most synoptic histories of the period fell silent about the evolution of technique after the 1920s and concentrate on the emergence of certain genres, such as the musical and the film of social comment.

Even André Bazin could be said to accept the premises of step-by-step artistic progress. Bazin showed that sound cinema wasn’t a dead end, that new artistic possibilities were exploited in the 1930s and 1940s. These were mostly creative alternatives to editing-based technique: the long take, extended camera movement, deep-space staging, and deep-focus cinematography. Bazin claimed that these techniques were most fully on display in the works of Renoir, Wyler, Welles, and some Neorealists.

Sarris was deeply influenced by Bazin’s ideas, but he didn’t accept the conception of film history as an accumulated technical evolution. Sarris called this the “pyramid fallacy,” with each filmmaker adding his slab to the rising and narrowing edifice of cinema. Instead, he proposed thinking of film history as an inverted pyramid, “opening outward to accommodate the unpredictable range and diversity of individual directors.”

In practice this demands that the historian survey entire careers, especially the works of ripe old age. It demands that the historian plot directors’ creative trajectories as paralleling and intersecting and overlapping—perhaps coalescing into broader trends, perhaps creating dead ends. The cinematic universe expands with each new film made, every old film rediscovered or simply re-seen. Auteurism “places a premium on having seen every work by a director who is deemed worthy of a study in depth; and by the time all the cross-references have been pursued in every possible direction auteurism seems to insist that every film ever made is relevant to the inquiry.”

Film history becomes less a linear progress toward something than a vast network of affinities and differences. This idea naturally led Sarris the writer not to the mammoth survey but to multifaceted essay collections. His big book, “You Ain’t Heard Nothin’ Yet,” looks like a panoramic history but is in fact a free-range miscellany, a sort of unbuttoned late-career redo of that Film Culture issue..

You can argue that Sarris was proposing a non-historical history, one that dispenses with concepts of influence and cause and that pulverizes any coherent narrative. That seems to me a valid objection. Despite its claim to be a theory of film history, Sarris’s auteurism strikes me as a historically informed approach to film criticism. The ultimate aim isn’t a convincing historical narrative but a compelling aesthetic judgment. Sarris’s idea of expanding filiation, infinite comparison and contrast, allows him to pursue what matters: evaluation.

In this respect at least, he’s agreeing with his predecessors, the writers who saw history as linear progress. But his criteria of value are different. For the traditionalists, the filmmakers who grasped the next step that the medium should take in its creative development become the best. For Sarris, the best filmmakers used the resources at their disposal to create valuable works that also displayed a distinct conception of human life. “Griffith, Murnau, and Eisenstein had different visions of the world, and their technical ‘contributions’ can never be divorced from their personalities.” Innovation was secondary to expression, and expression could best be gauged by tracking the wayward currents of the history of film style.

Auteur, yes; but of what?

New York Film Festival 1966: Pier Paolo Pasolini, translator, Andrew Sarris, and Agnes Varda. Photo by Elliott Landy. From Film Culture no. 42 (Fall 1966).

The auteur “theory” creates a decentralized and dispersed conception of film history—not a tree with a solid trunk and clear-cut branches but a bristling, tangled bush. The historian will dissolve big changes and broad trends into the doings of particular film artists. Who are these artists? Well, obviously, directors.

This move shouldn’t have been controversial. Critics had long assigned primary creative responsibility to directors. In the 1910s Louis Delluc heaped praise on DeMille and Sjöström, while Griffith was acknowledged around the world as a great innovator. Later von Stroheim, von Sternberg, Eisenstein, Pabst, Clair, Welles, Hitchcock, Maya Deren, and many other filmmakers were recognized as the artistic authority behind their work. In the early 1950s, foreign-language filmmakers such as Kurosawa and Bergman were identified (and even promoted by their distributors) as all-powerful creators saying something through their art.

Sarris’s real innovation was, along with the critics around Cahiers du cinéma and Movie, to transfer the idea of the expressive film artist from the headier regions of art cinema to the jostling, compromised world of Hollywood. There were obvious objections.

*Filmmaking is a “collaborative” activity, so you can’t attribute the final work to a single hand.

Yet in the collaborative medium of opera we speak of a Zeffirelli production as opposed to a Peter Sellars one. Why can’t a film director be a synthesizing artist orchestrating the contributions of many other artists?

*But in opera and other theatre forms, you have a preexisting text, the script or libretto or score. Why isn’t the screenwriter the artist, as Shakespeare or Verdi is?

Because theatrical texts are designed to be instantiated on different occasions, while film scripts are written to be produced only once. The film’s final form includes elements of the script, but that final form, being cinematic, can’t be uniquely specified in verbal language. As we all realize, give the same screenplay to six filmmakers, and you get six different and equally free-standing films.

*Popular film can’t be compared to high art. Artistry demands control, and the novelist, the painter, and even the opera director will exercise complete control over the final work. A Bergman or Antonioni has the cultural clout to dictate every aesthetic effect, but the Hollywood filmmaker works as part of a larger process controlled by others. He is handed a script and shoots it, and not necessarily all of it; second-unit and visual effects staff have their input too. The producer may demand more close-ups. In the classic studio system, the director wouldn’t typically get final cut; the producer would shape the released film. All these conditions constitute barriers to artistic expression. The auteur theory, when applied to Hollywood, is deeply inappropriate.

One answer to this objection is that many directors, including some of the best ones, did have a good deal of control over their work: Hitchcock, Hawks, and others were their own producers and worked on their scripts and oversaw their post-production. Moreover, a director can control choices down the line in sneaky ways, as when Ford shot his films so that they could be assembled in only one way.

Sarris advanced another reply to the control objection. If it owed something to the Cahiers young critics, he articulated and practiced it more keenly than they. He proposed a critical method: Take as many films signed by the director as you can find. Attend to the way they exercise their craft, the way they tell their stories and convey their meanings. Seek out an expressive core that seems distinctive, even unique.

Most directors’ collected works won’t yield this. “Not all directors are auteurs. Indeed, most directors are virtually anonymous.” Only the best directors will display a distinct expressive quality. Hawks and Hitchcock evoke radically different worlds of action and feeling, just as Mozart and Rembrandt can.

Fifteen years after his initial statement on the matter, “Notes on the Auteur Theory in 1962,” Sarris suggested that the elusive concept of personality was not to be derived from the director’s biography. “I was never all that interested in the clinical ‘personalities’ of directors. . . . A director’s formal utterances (his films) tell us more about his artistic personality than do his informal utterances (his conversation).”

For example, we understand John Ford’s respect for what Sarris calls “codes of conduct” not through the old curmudgeon’s interviews but by confronting the tangible texture of the movies. One of Sarris’s favorite examples occurs in The Searchers. Drinking his coffee, the Ward Bond character glances toward the wife of the household. Then his point of view reveals her stroking the uniform of her husband’s brother, played by John Wayne.

Cut back to Bond as the wife and her brother-in-law meet for a tender farewell. Bond stares off into space, chewing.

“Nothing on earth,” writes Sarris, “would ever force this man to reveal what he had seen. There is a deep, subtle chivalry at work here, and in most of Ford’s films, but it is never obtrusive enough to interfere with the flow of the narrative.” The economy is part of the point. “If it had taken him any longer than three shots and a few seconds to establish this insight into the Bond character, the point would not be worth making.”

In the Hollywood studio context, there was something heroic about the rare director who could surmount all the pressures, filter out all the noise, and shape the impact of his work. “The auteur theory values the personality of the director precisely because of the barriers to its expression.” Like a great Renaissance painter paid by a pope or a duke and pledged to illustrate well-known stories, the Hollywood director working for a studio could occasionally conjure up something powerful and distinctive.

Auteurism, Sarris claimed, is our straightest road to determining a film’s value. The great films, by and large, will be those that evoke distinctive directorial sensibilities. But “by and large” allows for the possibility of excellent movies that we can attribute to other forces—script, stars, source material, the happy intersection of talents. Casablanca, writes Sarris, “is the most decisive exception to the auteur theory.” Sarris loved movies more than he loved his theories.

Compare, contrast, repeat

Sarris’s breakthrough essay, “Citizen Kane: The American Baroque,” appeared in Film Culture during the 1956 revivals of the film. This detailed explication, published when Sarris was twenty-eight, betrays his grad-school training at a period when the New Criticism reigned. In a single stroke, he pioneered the sort of close reading that would become central to Anglo-American academic film criticism.

I can’t recall any later Sarris essay offering such an intensive analysis of a single film. As he developed his historically-guided critical appraisals, he favored synoptic appreciations of directorial careers. These became the occasions for him to point out interacting directorial personalities that comprise that vast network of cinema.

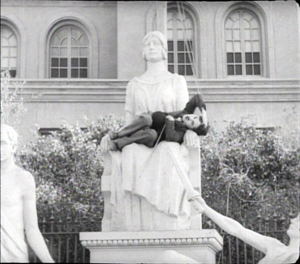

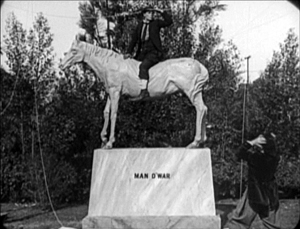

Instead of macro-analysis, Sarris embraced a strategy of “drilling down,” we’d now say, to a single revelatory passage. The chief tactic is comparison, often involving two directors faced with a comparable situation. Both City Lights and The Goat show a protagonist hiding on a statue about to be unveiled. Chaplin seizes the chance to deflate the ceremony.

But Keaton, says Sarris, is less interested in satire; he is “a pessimist in perpetual motion.” In The Goat, “Keaton remains mounted on the clay horse until it begins to sag and crumple under his weight, and the sculptor, a bearded nincompoop in a beret, proceeds to break down and weep.”

“Keaton’s expression here,” Sarris claims, “is mercilessly pragmatic. What good is a clay horse (art?) if you can’t mount it to your own advantage? There is something unabashedly ruthless about Keaton’s comedy, which chills his humor.” This was the period when critics, having just rediscovered Keaton’s films, claimed him as a “metaphysician.” Sarris likened him to Beckett.

Sarris wasn’t alone in turning to detailed commentary at the period; we had Dwight Macdonald’s appreciative 1964 essay on 8 ½ and John Simon’s book-length study of Bergman (1973). But Sarris got there early with the Kane piece, and throughout his career he used analysis to pinpoint authorial personality. Attention to nuanced differences allowed him to create a kind of connoisseurship.

The ultimate expression of this connoisseurship emerges in his concern for privileged moments. A critic has to be alert for shots or gestures or lines of dialogue that encapsulate the emotional tenor of a film and a director’s sensibility. Sarris’ example is a moment in La règle du jeu:

Renoir gallops up the stairs, stops in hoplike uncertainty when his name is called by a coquettish maid, and then, with marvelous post-reflex continuity, resumes his bearishly shambling journey to the heroine’s boudoir.

If I could describe the musical grace note of that momentary suspension, and I can’t, I might be able to provide a more precise definition of the auteur theory. As it is, all I can do is point at the specific beauties of interior meaning on the screen and later catalogue the moments of recognition.

No director but Renoir, Sarris suggests, would have Octave break the scene’s rhythm in exactly this way–and in a manner, Sarris’s bear-metaphor hints, that anticipates Octave’s costume for the climactic party in the chateau. The nonchalant, slightly awkward interruption epitomizes Renoir’s entire style of filmmaking, which has room for casual deflections from neat plotting and groomed performances. The critic’s words can’t wholly capture the force of Octave’s hop, and its resonance for Renoir’s film and his oeuvre. It is, says Sarris, “imbedded in the stuff of cinema.”

Both cinephiles and ordinary viewers are seized by luminous instants that change our skin temperature. We come out of a film satisfied if a few epiphanies have flashed upon us. The critic can signal them but not explain them fully. Interior meaning is the product of craft and personality, but it can’t be reduced to them. It creates a tingling, fugitive beauty that is unique to cinema.

Everyone has his or her own Sarris. The foregoing offers merely bits of mine, and they’re largely academic in slant. That’s because I think that Sarris changed, among other things, the way film history and criticism were taught in American universities. While Kael influenced film journalism, particularly in the upscale markets, Sarris’s legacy is best seen in cinephile criticism (Film Comment, Film Quarterly et al.) and academic film studies. Some Paulettes went to work for the New York cultural weeklies, high and low. Many people who were Sarrisites to some degree (Jeanine Basinger, James Naremore, John Belton, William Paul, Elisabeth Weis, Chuck Wolfe, Mark Langer, Robert Lang, et al.) became professors. Kael’s followers turned out essays, but Sarrisites like Todd McCarthy and Joseph McBride wrote books based firmly in research. Sarris’s version of auteurism has been reworked, in plenty of intriguing ways, in directorial monographs from university presses. He once remarked ruefully that he was an academic among journalists and a journalist among academics, but he managed to bridge the gap adroitly.

Sarris was too far-out for the New Yorker in 1965, and probably for the New Yorker of today. But history, and not just the history of movies, was on his side.

David Bordwell

blog comments powered by Disqus